Michele Forman grins as the plates arrive at the table. Grilled oysters. Pasta Bienville with a side of mustard greens. And Pasta on the Bayou, a house favorite.

In a restaurant a block off Main Street, not far from picturesque Courthouse Park in Houma, Forman courts her visitors with Cajun food while providing a glimpse into her inspiration.

“My mom was probably the best cook I ever knew,” said Forman, the proprietor of Mimi’s Creole Café and Oyster Bar. “Everyone came to our house growing up, just to eat her food. It got so popular, she’d hire people to drive around town and deliver the meals she prepared.”

Forman grew up on nearby family land, where her father raised crops. When critters began eating the crops, he set out to trapping the pesky nutria, minks, otter and possum and discovered another source of revenue as a trapper. And he made it home every night in time for a can’t-miss supper at Mimi’s table.

A main dish of chicken with cabbage and a cornbred muffin on a bed of rice at Mimi's Creole Cafe./ GARY TRAMONTINA PHOTOS

Char-grilled oysters are one of Mimi's specialties.

Mini cornbread muffins at Mimi's melt in your mouth.

Owner Michele Forman outside Mimi's Creole Cafe, a popular downtown restaurant.

A blue-haired angel pulls sentry duty at the Chauvin Sculpture Garden outside Houma.

Some of the unique art found at Chauvin Sculpture Garden.

Alligator head souvenirs at The Shack, another can't-miss Houma restaurant.

Forman’s mother passed away recently, but the tradition lives on seven days a week, thanks to the recipes that remain behind and the talent of Foreman’s chef husband, Charles.

That’s why regulars return and newcomers seek Mimi’s café out.

“Food is a unique expression,” Forman said. “We cook with Cajun seasonings, and everyone loves it. Like my mom always said, ‘Cajun cooking is food for the soul.’”

In Houma, Cajun food is a staple, from fine dining to family fare found at The Shack. Even Walk-Ons, the popular sports bar based in nearby Baton Rouge, is primed with Cajun offerings.

It’s a popular culinary style that has ties back to Louisiana’s earliest – and darkest – days.

“It’s About Triumph”

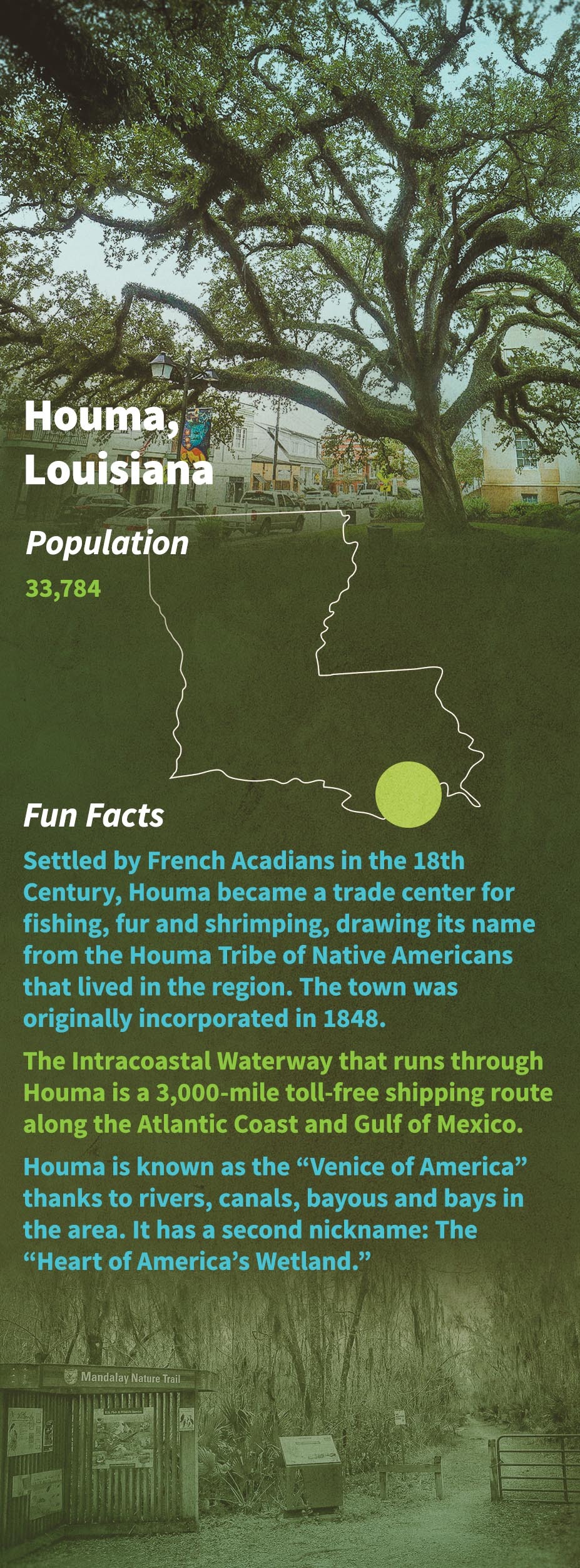

Just under an hour southwest of New Orleans, Houma is on the edge of the bayous of Terrebonne Parish, where Spanish moss drapes trees and million-dollar homes back up to canals flowing into the Intracoastal Waterway, then south into Tambour Bay. Drawbridges cross the water every few miles, and pleasure craft eventually give way to shrimpers and crab boats that provide sustenance to the region.

Colonists claimed the land before Acadians from France, seeking more freedom, migrated from Canada and began settling. The Cajuns gave the region much of its cultural flavor.

But, according to historian Margie Scoby, what we now know as Cajun food was a blend created by another population that settled here against their will.

“When you think about Cajun cuisine, it’s hard to separate it from slavery,” said Scoby, the President of Finding Our Roots African American Museum. “Think about the origins of gumbo. It’s a mess, and it was meant to be, because whatever leftovers the master sent to the slaves had to be creatively made into meals that could feed large numbers. That’s why we call Cajun food here ‘soul food.’”

As a child, Margie Scoby was told she would grow up to become a griot, or storyteller. Now she shares stories with visitors at the Finding Our Roots African American Museum./ GARY TRAMONTINA PHOTOS

Alvin Tillman shares history, explaining the daily routine of slaves in Louisiana.

Alvin Tillman and Margie Scoby sing "Wade in the Water." Spirituals like this provided hope for an enslaved population, but also included top-secret intel.

The Finding Our Roots museum tells the story through the lens of African Americans in Louisiana, including history that remains painful to this day.

A sclupture of a detached hand and a legal pamphlet from the era before Emancipation provide examples of how slaves were treated as less than human.

Located in the century-old Fifth District High School, the first school for African Americans in the parish, Finding Our Roots immerses visitors in the African American experience. The artifacts and displays are gripping and powerful. The museum offers a somber reflection of the cruelties and injustices suffered by African Americans during America’s days of slavery and the times of segregation that followed. Visitors learn, for instance, about how thousands of people from Africa were brought into Louisiana by way of white Northeastern U.S. companies to work the sugar cane fields.

There are also tributes to those who overcame adversity and advanced the cause of equality. Visitors are introduced to Houma native Gerald “Coke” Riley, who became a famous Hollywood hairstylist; Oscar James Dunn, the first African American elected to a statewide office as lieutenant governor in 1868 – at the height of Reconstruction; and James Cage, a prominent white businessman who helped slaves escape along the Underground Railroad. Famous athletes, business leaders and religious leaders are also honored.

Scoby was 7 when she was told that she had to listen and absorb the stories of the past and pass them on — for she would carry on the family tradition as a griot, the West African term for storyteller.

Long before phones or the telegraph, there was the slave bell, the chief form of communication. It rang in the morning to signal the start of the day; it rang at noon for lunch, and it rang at sunset. This artifact was donated by a local pawnbroker. “We beg, we rummage, we do anything short of stealing to find what we have,” Scoby said.

Alvin Tillman Sr. was the first African American chairman of the Terrebonne Parish Council. Now he’s the vice president at Finding Our Roots. He joins Scoby for the final exhibit, the Echo Circle. They sit with their audience around a washtub and begin signing the spiritual Wade in the Water. The music is moving, even more so when they explain the experience.

In the 1800s, the ways the songs were sung provided clues to other slaves – when they were safe, when they could flee and routes to take. The clues went deeper, as lyrics and melodies carried other hidden meanings as they echoed for miles.

“We pride ourselves on telling these stories and sharing the past with those who come here,” Tillman said. “What you learn is that this isn’t about slavery, it’s about triumph.”

Swamp Tours — Everywhere

You can’t visit Houma without taking an airboat tour. The History Channel has made Swamp People must-see TV, and two of its stars, Houma natives R.J. and Jay Paul Molinere began offering tours through their new venture.

Other swamp tours are plentiful, as are fishing charters either on the bayou or out in open water, easily accessible from dozens of marinas.

For a more leisurely exploration of the bayou, the Mandalay National Wildlife Refuge offers trails, boardwalks and a covered bridge tour that’s great for gator observation and bird watching. Come at the right time, and creep quietly, and you’ll find river otters and nutria, eagles and osprey, and reptiles that go “snap“ in the night.

The people, the culture, the accents and the terrain all make Houma unique, luring filmmakers, as well. In the last quarter century, the list of films made in and around Houma include Robert Duvall in The Apostle, Melanie Griffith and Lucas Black in Crazy in Alabama and Brad Pitt in Fight Club.

Another view, unlike any other, of the water adjoining the nature trail at Mandalay./ GARY TRAMONTINA PHOTOS

From a covered bridge, the view of the marsh at Mandalay Nature Trail.

Handy markers help visitors to the Mandalay Nature Trail identify local wildlife.

The entrance of the Mandalay Nature Trail in Houma, where one can get a feel for being deep in the bayou while only a few minutes from city life.

Further speaking to the area’s reputation and mystique, fans of The Suicide Squad know the backstory of Harley Quinn and her gang originated at Houma’s Bell Reve, the fictional maximum-security prison on the site of an old plantation used to house metahuman criminals.

But if wildlife and D.C. Comics aren’t your thing, keep heading south along Little Caillou Road to discover Chauvin Sculpture Garden. It’s here, along the banks of the Bayou Petit Caillou, that a Vietnam veteran named Kenny Hill left behind more than 100 quirky concrete pieces of art depicting his take on spirituality, while reflecting his own personal pain. Hill squatted on the land in a tent, then built a small cabin, keeping his work private until he was eventually evicted.

Now under the direction of Nicholls State University, the folk art left behind is adorned with angels, cowboys, children and soldiers who entice you to explore.

But, keep in mind, this is just a pitstop on the journey.

“This has always been home”

You can access Cecil Lapeyrouse Grocery Inc., by boat, thanks to a dock on the bayou. During peak season (June, July and August), 75 percent of business comes from the water. The rest comes by car, arriving at a building that maintains the charm of a 106-year-old edifice. A garden Lapeyrouse’s wife first created in 2000 greets the boat traffic.

“When my grandfather first built this, there was no road. Everything was done by water,” said Lapeyrouse. “Supplies came by boat from New Orleans once a month. Now, it’s a gathering place. We talk about what’s going on in the world over coffee.”

Born in Terrebonne Parish, Lapeyrouse is the third-generation owner, taking over in 1987. He’s accompanied by his son, Ty Trosclair, a charter fishing captain enjoying downtime due to a wet, wintry day. Every move is followed by two dogs. Drew is named after New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees, of course. And Little C was given the name by one of his grandchildren. “We’ve been pet sitting these dogs for seven years,” Lapeyrouse offers in a playful harrumph.

In 1926, a hurricane flooded the grocery, which is on the highest spot for miles, rising a foot above the counter. But Hurricane Katrina did the opposite, pulling the water out of the bayou as it roared east toward New Orleans and Mississippi.

The front entrance of Cecil Lapeyrouse Grocery for those who opt to visit by car./ GARY TRAMONTINA PHOTOS

Fisherman Ty Trosclair and the grocery store's namesake, Cecil Lapeyrouse, share a laugh with a customer while Drew the dog sleeps away a rainy day.

Cecil Lapeyrouse shares vintage photos from the grocery store's early days.

The garden behind Cecil Lapeyrouse Grocery, where many customers arrive by watercraft.

Sprawling, centuries-old trees frame the entrance to the Terrebonne Parish Courthouse.

Water dominates everything. Lapeyrouse estimates there are only 40 full-time residents in his community — the rest are weekenders and recreational fishermen. And the water that brings life to the bayou now imperils its existence.

Across the dock, on the other side of the canal, dying oak trees stand where sugar cane used to reign. Saltwater invading the land has killed the roots of the trees, and freshwater vegetation, once abundant, is rare. And the water continues to encroach.

“This is about environmental change,” Lapeyrouse said. “You used to have sugar cane grown on both sides of us. Now, it’s more fit for shrimping and crabbing. The water flows more freely, because we’ve lost our barrier islands and buffers.”

Once upon a time, you could take a horse and buggy down a dirt road to reach a fishing resort on one of the barrier islands south. Now the paved road ends five miles from here, and some of the once-thriving barriers are small sandbars. In a few years, more land will recede.

Certainly, the past is historic, and the future is uncertain. Yet Cecil Lapeyrouse Grocery, Inc., and its owner, aren’t going anywhere. “This has always been home, and always will be.”